Worlds of Homelessness

Housing Justice in Unequal Cities

Housing precarity is not a new phenomenon. In a series of essays titled “The Housing Question,” which were published as a pamphlet in 1872, Friedrich Engels noted that structures of housing shortage and geographies of urban displacement were a necessary accompaniment of capitalism.

By Ananya Roy

Engels’s uncanny analysis, as relevant today as it was for the industrial city of the late 19th century, is rooted in his own confrontation with social difference. Son of a wealthy German industrialist sent to observe the cotton industry of Manchester, his encounter with inequality and exploitation at this node of colonial capitalism was to set into motion a formidable critique of the institution of housing, including of various bourgeois reforms meant to allay the crisis of slums and poverty.

What is the housing question of the early 21st century?

The second is the criminalization of poverty. In cities around the world, the urban poor face stigmatization and exclusion, often through the use of legal reason and legal authority deployed by municipal governments. Framed as encroachers, the unhoused and informally housed are positioned as violations of spatial and social order. Such forms of criminalization are especially harsh today in U.S. cities, with Los Angeles bearing the dubious distinction of pioneering cruel and harsh policies of banishment that deny rights to those on the margins of propertied citizenship. Indeed, in Los Angeles, a series of municipal ordinances have turned houselessness into a state of social death, without the constitutional protections and civil rights that accord to those who are housed.

Both these processes – the financialization of land and housing and the criminalization of poverty – must be placed within the present history of racial capitalism. Engels’s analysis of the housing question, despite its brilliance, is glaringly silent on one point: that Manchester was not only the scene of capitalist exploitation but also that it was a node of colonial capitalism, linking the industrial city of England to the ravaged hinterlands of the British empire. One form of exploitation was deeply linked to another form of dispossession. Today, in many cities around the world, especially in the United States, the contours of financial exploitation are the through-lines of racial and ethnic segregation. Today, in many cities around the world, especially in the United States, carceral power is directed at racial others and can be understood as the after-life of slavery and colonial conquest.

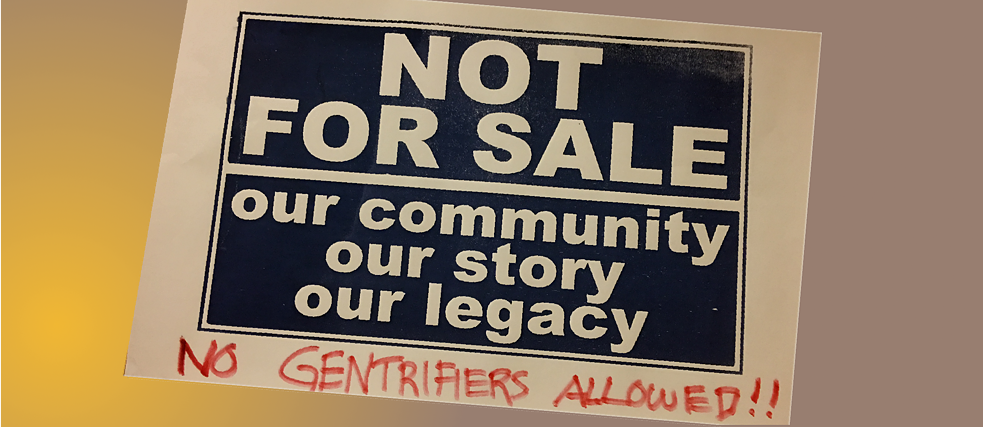

If such processes constitute today’s housing question, then what is housing justice in unequal cities? It is precisely this question that animates a new global research network situated at the Institute on Inequality and Democracy at the University of California, Los Angeles, for which I serve as director. We view the present historical conjuncture as a moment not only of substantial housing precarity but also of an extraordinary proliferation of housing justice movements. Often connected across national borders, these movements constitute the frontlines of urban struggle. They are fighting for rent control and social housing. They are challenging the rightlessness of the unhoused. Most significant, they are crafting new meanings of property and rent, personhood and tenancy. With the uncanny analysis that Engels once demonstrated, they are pinpointing the structures of wealth accumulation for which housing precarity is a necessary accompaniment. Rejecting bourgeois reforms, these movements, from Los Angeles to Berlin, Barcelona to Durban, Rio de Janeiro to New York, are mobilizing instruments of expropriation to insist upon the social function of property and to command the decommodification of housing. Inevitably, such movements are in alliance with those striving for racial justice and climate justice. Together, they could very well rewrite today’s housing question.

Housing Justice in Unequal Cities

Housing Justice in Unequal Cities is a global research network funded by the National Science Foundation (BCS 1758774) and housed at the Institute on Inequality and Democracy at UCLA Luskin. This open-access volume, co-edited by Ananya Roy and Hilary Malson, brings together movement-based and university-based scholars to build a shared field of inquiry focused on housing justice. Based on a convening that took place in Los Angeles in January 2019, at the LA Community Action Network and at the University of California, Los Angeles, the essays and interventions situate housing justice in the long struggle for freedom on stolen land. Embedded in the stark inequalities of Los Angeles, our work is necessarily global, connecting the city’s Skid Row to the indebted and evicted in Spain and Greece, to black women’s resistance in Brazil, to the rights asserted by squatters in India and South Africa. Learning from radical social movements, we argue that housing justice also requires a commitment to research justice. With this in mind, our effort to build a field of inquiry is also necessarily an endeavor to build epistemologies and methodologies that are accountable to communities that are on the frontlines of banishment and displacement.

Source: Institute on Inequality and Democracy at UCLA Luskin

The full program of the conference as well as more information on the Network, and how to join it, are available

here.

Download the PDF of this open-access volume, co-edited by Ananya Roy and Hilary Malson:

© Institute on Inequality and Democracy at the University of California, Los Angeles