Real-World References in Dance

Skill and Form

The objection is repeatedly raised to contemporary dance that it is too preoccupied with itself and fails to make references to the realm of experience outside the world of art. In a major study, Stefan Apostolou-Hölscher has examined the historical development of real-world references and aesthetics in dance. It claims that the lack of real-world references in dance is much older and that it already began with the founding father of dramatic ballet, Jean Georges Noverre.

The objection is repeatedly raised to contemporary dance that it is too preoccupied with itself and fails to make references to the realm of experience outside the world of art. In a major study, Stefan Apostolou-Hölscher has now examined the historical development of real-world references and aesthetics in dance. It claims that the lack of real-world references in dance is much older and that it already began with the founding father of dramatic ballet, Jean Georges Noverre.

Before dance began to develop into ballet as a distinct art form in eighteenth-century France, it had fulfilled what was primarily a political mission in the pre-absolutist age: to discipline the aristocracy while illustrating the absolutist power structure to which the aristocracy laid claim. Thus, the ballet movement was a “power-knowledge structure“ that exploited the body and its exaltation in the ballet movement – and thus also its submission to a choreographic regime - in a very direct and crude way. As a countermovement to this purely functional status, which was reduced to political aspects, Jean Georges Noverre postulated his aesthetic model of ballet d’action in the mid-eighteenth century. It marked the beginning of a transformation that led dance into the field of the fine arts for the very first time.

The truth of the living

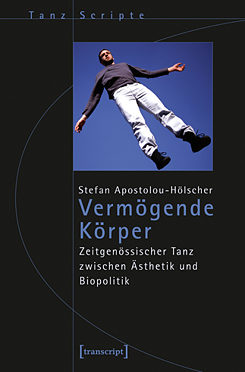

In his Letters on Dancing and Ballets of 1760, Noverre postulated an orientation of dance to life itself, to the ‘truth of the living’ instead of to mere virtuosity. What is conspicuous from today’s perspective is his paradoxical demand for “naturalness“ in body control and the primacy of action, of ongoing happenings in the sense of narrative. The distinctive features of dance should no longer be allegory and symbolism, or pomp and grandeur, but “natural truth“ as a series of actions, ballet d’action. Stefan Apostolou-Hölscher: Vermögende Körper. Zeitgenössischer Tanz zwischen Ästhetik und Biopolitik. Bielefeld: Transcript 2015

| © Transcrip Verlag

“Natural truth“ is not to be equated with realistic presentation, however. Rather, the artist should improve on nature through selection, emphasis, compression, streamlining and motionlessness, relying on “taste“ and “charm”. Yet these guiding qualities cannot be taught, just as a person’s physical aptitude for the profession of dance, in Noverre’s view, cannot be acquired through training. While the dancer has be able to stand in a way that is “poised” and “beautiful”, that is a natural talent, not the result of training.

Stefan Apostolou-Hölscher: Vermögende Körper. Zeitgenössischer Tanz zwischen Ästhetik und Biopolitik. Bielefeld: Transcript 2015

| © Transcrip Verlag

“Natural truth“ is not to be equated with realistic presentation, however. Rather, the artist should improve on nature through selection, emphasis, compression, streamlining and motionlessness, relying on “taste“ and “charm”. Yet these guiding qualities cannot be taught, just as a person’s physical aptitude for the profession of dance, in Noverre’s view, cannot be acquired through training. While the dancer has be able to stand in a way that is “poised” and “beautiful”, that is a natural talent, not the result of training.In any case, what is more important than the artistically given form of imitation is to imitate the ability of nature itself as natura naturans (nature that creates nature) to produce ever new forms. Nature is the imitative principle that is to be imitated. This concept of naturalness as the subject of imitation is an aesthetic demand, however, and thus a genuinely artistic concept rather than a “natural” one. This productive discrepancy ultimately concerns the question of how the “natural“ body is made “artistic“, making bodies “something“ that they are not “by nature“.

The void of art

This is the starting point of the analysis by Stefan Apostolou-Hölscher. In his book Vermögende Körper (Skilled Bodies), he describes the strange “artifaction” of nature, which always remains a mystery. A “void“ is created where poetological or academic conventions are no longer regarded as the standard, but the surpassing of standards itself becomes the standard. No definition is given of what this means, however. A dancer or artist is subject to a numinous regime of control without recourse to a higher instance except that of “naturalness“ – “this moment of naturalness […] innate to all human beings, [...] that always reveals itself with as much energy as truth“, as Noverre put it.Further developing this model involves constantly dealing with “effect(s) of normative rules for the production and reception of dance”, says Apostolou-Hölscher, “which have time and again established in different ways the relationship between choreography as a form and dance as an activity […].“ In the artistic field, the creation of forms is not random, and above all, it is not purposeless: the forms generated in each case are used – for dance performances in the case of Noverre and ballet d’action. But in the process, the body and its truly “boundless” ability inevitably empower their design.

Indefinite liveliness, definite life form

It is within this historical context that Apostolou-Hölscher develops his observations on the regime of dance as biopolitics, as a form of defining physical ability that always shows less than the body’s potential. The “living activity of bodies as their inherent skill“ provokes in them “an indefinite liveliness that cannot fulfil itself in any particular life form“. Choreography is precisely such a “particular life form“, however. Apostolou-Hölscher shows that contemporary artists, too, from Yvonne Rainer to Mette Ingvartsen and Jérôme Bel to Ivana Müller, operate using this dichotomy.Recurring hermeticism, the intractable foreignness of dance at odds with form and specification, is thus an echo of liberation, the release of ballet from its purely courtly function as a symbol of power. According to Apostolou-Hölscher, however, freedom can never occur in a particular form and that is precisely why, even today, there must always be distance between dance and form. Possibly only an observer can bridge this divide.

Stefan Apostolou-Hölscher: Vermögende Körper (Skilled Bodies). Zeitgenössischer Tanz zwischen Ästhetik und Biopolitik. Bielefeld: Transcript 2015. 395 pages.