Josef Leisen

Language-sensitive CLIL means learning from the foreign languages

What is CLILiG?

CLILiG is an acronym for Content and Language Integrated Learning in German. It is one educational approach to integrated (foreign) language and (subject-specific) content learning, in this case through the medium of German as the foreign language. CLILiG involves teaching a subject in a language – in this case German – that is not the native tongue of the learners and/or the teacher. The teacher may be qualified as a language and/or subject teacher. The learners and the teacher are not normally immersed in the foreign language (German) in their everyday lives. The CLIL approach is closely related to bilingual content teaching and to the German-language content teaching (DFU) that is offered for example at the German Schools Abroad.This makes it clear that CLILiG is not content-based language teaching, but language-based content teaching. This entails certain prerequisites with respect to the teacher’s expertise. Teachers must have expert knowledge of the subject content itself, as well as a high level of language proficiency in the teaching language – in this case in German (German tends to be the mother tongue of teachers at the German Schools Abroad). From this perspective, it is not essential that the teacher also have foreign language teaching skills. However, this is a requirement in standard bilingual classes in Germany, and is a prerequisite for attaining the necessary permission to teach a bilingual class.

“The conditions for German-based content learning, that is to say the learning of content in German, and for content-based learning of German, differ greatly, as the following questions illustrate:

- Do the pupils have German as their native tongue, or a foreign language?

- Do the teachers have German as their native tongue, or a foreign language?

- Is the teacher qualified as a content teacher and/or as a language teacher?

- Do the pupils live in a German language environment (full immersion) or not?

- Are the pupils first or second learners of the subject?

- Are the learners at a rudimentary or an advanced language proficiency level?

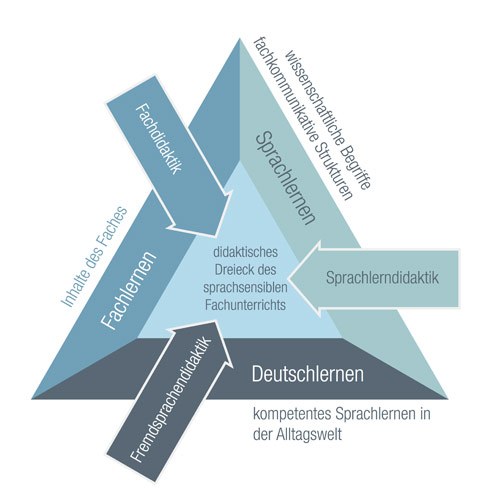

Integrated content and language learning in CLIL lessons

Integrated content and language learning in CLIL lessons encompasses:- Content learning: learning and understanding the content of the subject in question, and gaining insights by means of the specific methods used in the subject (e.g. deductive, inductive, hermeneutic, heuristic, experimental methods …)

- Academic language learning: learning the way in which the subject content is presented, how terms are created, the technical terms and specific language structures used in the subject (e.g. deoxyribonucleic acid, the apparent weight loss brought about by buoyancy …) and the linguistic peculiarities in the written language register

- German learning: competent language learning in the target language, in this case German, in the spoken language register.

- Content didactics: the teaching and learning of the subject content

- Academic language didactics: the teaching and learning of the technical language used in the subject

- Foreign language didactics: the teaching and learning of German as a foreign language

© Josef Leisen

Teachers with an expert knowledge of all three didactic approaches are predestined for CLIL teaching. It can rightly be claimed then that learning how to teach CLIL means learning from the foreign languages. In foreign language didactics there are principles that foster learning effectively in any content lesson. We will take a closer look at these principles next – they play an important role not only in CLIL, but in any content lesson taught in the learners’ native language.

© Josef Leisen

Teachers with an expert knowledge of all three didactic approaches are predestined for CLIL teaching. It can rightly be claimed then that learning how to teach CLIL means learning from the foreign languages. In foreign language didactics there are principles that foster learning effectively in any content lesson. We will take a closer look at these principles next – they play an important role not only in CLIL, but in any content lesson taught in the learners’ native language. Learning from the foreign languages

Foreign language research has established an entire series of principles and has used studies to demonstrate their effectiveness (cf. Funk, Hermann inter alia, 2014). Some of the principles of particular relevance to CLIL are listed below.Competency orientation

- Competencies refer to those cognitive abilities and skills that people need to overcome problems, and to their willingness to successfully overcome problems in different situations.

- Competency = knowledge + willingness + action

- Competency is the active use of knowledge and values.

Success orientation and calculated challenges

- Success gives satisfaction, motivates and strengthens self-confidence.

- Abilities must grow to the same extent as the requirements (calculated challenge principle).

- Tasks and exercises must be geared towards success, i.e. they should produce successful learning products, though these do not necessarily have to be error-free.

Action and learning product orientation

- If competency involves performance, lessons must get learners to actively use the language.

- Tasks can be set to put learners in situations and introduce them to topics that are relevant to the learners themselves, and which also occur outside the classroom.

- When learners become active, learning products are the result (reading, writing, language products).

Task orientation

- Tasks are used to get learners to actively use the language, creating language products in the process.

- Tasks must reflect the calculated challenge principle.

- Well-researched quality characteristics are available to ensure the quality of the tasks.

Interaction orientation

- In lessons, tasks are used to inspire learners to communicate with one another and to act within a social context.

- Learners experience themselves as active language users.

- The social relationships and communication culture are crucial in determining the quality of the interaction.

Learner activation

- Learners are actively involved in helping to shape the lesson.

- They contribute their own ideas, ask questions, produce language products, enter into discourse on language products, invent rules, check learning success etc. Learners assume teacher activities and steer lesson processes.

Language-sensitive CLIL teaching is aimed at language learning within a particular subject under these conditions. Consequently, language-sensitive content teaching is based on three basic principles of language acquisition, which in turn are based on the principles of foreign language teaching:

- Learners are put in language situations which, while authentic within the particular subject context, are manageable (they are immersed in the technical language of the subject). (Immersing learners in the technical language in this way encompasses a wide range of lesson situations involving intensive communication within and about the subject field. Relevance to the principles of foreign language teaching: interaction orientation, learner activation, action and learning product orientation)

- The language requirements are marginally higher than the learners’ individual language abilities (relevance to the principles of foreign language teaching: task orientation, competency orientation, success orientation and calculated challenge, according to Krashen 1985, cf. also Leisen 2013, p. 67).

- Learners are given the language help they need – if they exert themselves – to overcome the language situations, though not necessarily without making mistakes (scaffolding, language support, methodological tools; reference to the principles of foreign language teaching: task orientation, learner activation).

- Language situations that are authentic within the particular subject context are created at a language and content level that is suitable for fostering the development of content- and language-related competencies (standard language situations).

- Tasks are designed and learning materials and methods are created for these learning situations (tasks, change in forms of presentation, methodological tools).

- Content and language learning is supported with the aid of materials and staff (methodological tools, scaffolding, supervision of learning processes, language level diagnosis, formative assessment).

Foreign language teachers have expert knowledge of how this can be achieved – knowledge from which subject teachers can learn.

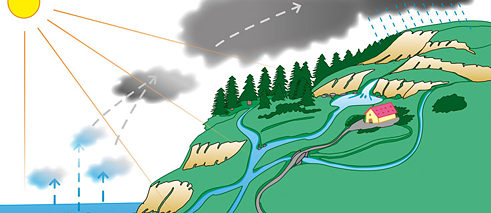

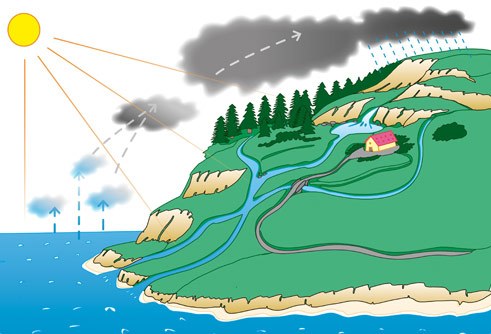

Example: the water cycle

© Alexander Weiler

Aufgaben:

© Alexander Weiler

Aufgaben:

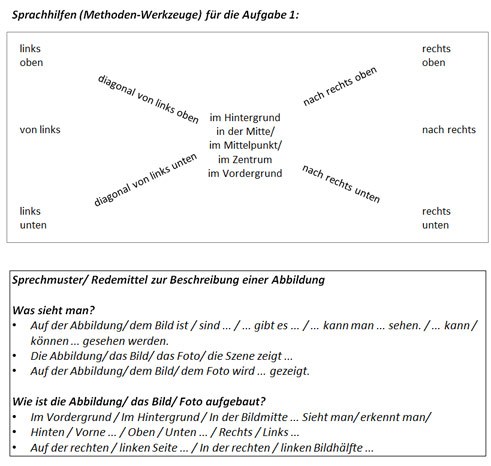

- Beschreib die Abbildung!

- Beschreib den Kreislauf des Wassers!

© Josef Leisen

© Josef Leisen

© Josef Leisen

Erläuterungen:

© Josef Leisen

Erläuterungen:

- Lernende brauchen Wortschatz und vor allem Verben mit Präpositionen. Nur mit Verben lassen sich Sätze bilden.

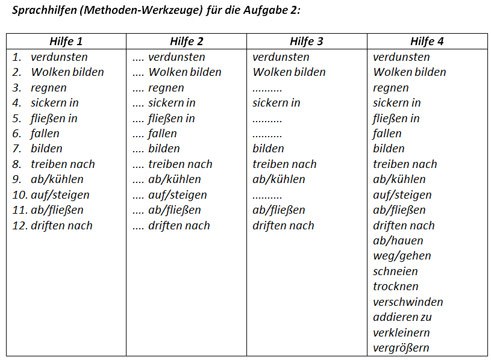

- In der Abbildung nummeriert die Lehrkraft die zwölf Prozessschritte mit den Zahlen 1 - 12. Fachlich und sprachlich schwache Lernende erhalten die Hilfe 1. Damit ist die fachliche Richtigkeit gesichert, und die Aufgabe beschränkt sich auf die sprachliche Formulierung.

- Je nach fachlichem und sprachlichem Können erhalten die Schüler/-innen abgestuft die Hilfen 2-4. Überzählige Verben sind für die Lernenden eine Erschwernis.

Commonalities and differences

Aspects that language learning in a foreign language lesson and a CLIL lesson have in common are their basic principles, their sensitivity to language obstacles, their awareness of the need for linguistic support (scaffolding) to ensure the successful active use of language, and their need to create a diverse and inspiring immersive environment.There are also differences between language learning in a foreign language lesson and language learning in a content lesson.

Language learning in a foreign language lesson:

The language situations that learners experience in their everyday lives and their knowledge of the world determine how they think and the scope of the language they use or should use. The teacher can – especially in rudimentary level classes – adapt the “language world” to the language proficiency level of the learners.

Language learning in a content lesson:

The language situations encountered within the subject context and the subject content determine the way learners think and the scope of the language used. The teacher can only adapt the “language world” to the language proficiency level of the learners to a limited extent, and must familiarize learners with this language world. Within the language world of the content lesson, linguistic structures occur early on (e.g. the passive form) that have not yet been covered in foreign language lessons. Specific linguistic structures such as “a force is exerted upon” have to be used as a result of the subject. An everyday and specialist vocabulary is needed to describe phenomena, e.g. processes of evaporation and condensation, yet this vocabulary has not yet been covered in foreign language lessons, and is difficult to paraphrase using everyday terms in the foreign language.

Another difference concerns the linguistic registers of spoken and written usage primarily related to the active use of the language.

- Everyday language usage encompasses: talking, telling, ranting, grumbling, tweeting, chatting, ordering, telephoning, conversing, reading, writing ...

- Academic language usage encompasses: reporting, describing, reasoning, arguing, verbalizing, modelling, discussing, explaining, documenting, reading, writing ...

Example: calorific value of peanuts

Task: Determine the calorific value of peanuts, proceeding as follows:

- Within your group, come up with ideas for a suitable experiment. The box of materials contains more apparatus than you will actually need.

- Think about potential causes of error, and how the apparatus could be optimized.

- Present your test apparatus and how you plan to conduct the experiment to the class.

- You should all describe the test apparatus and the planned experiment in your books.

- You will then be given a test apparatus with a description from the book. Compare your setup and explain any optimization.

- Conduct the experiment.

Understanding the subject is the challenge in CLIL

A CLIL lesson is only as good as its ability to enable the learner to understand the subject. This is precisely where the great challenge lies, which can lead to a vicious circle if not overcome: a lack of language proficiency results in a failure to understand, the lack of understanding causes the learner to fall behind, and this falling behind ultimately results in exam failure.The linguistic challenge for CLIL is to bring about an early and essential switch in register from spoken to written use or, to put it another way, from everyday language to academic language. If learners remain in the everyday language register they will not be able to do justice to the subject – but an abrupt switch to the academic/technical language register will not do justice to the learners. What is needed is an intermediate language, namely the language of instruction.

The language of instruction is everyday language interspersed with elements of the academic/technical language. The language of instruction is the language used to support the process of understanding, while the technical language is the language used once the subject content has been understood.

Example:

In the classroom, pupils might describe the block and tackle system rule that they have understood from their experiment as follows: “I count how many rope parts there are to the right and left of the moving block and divide the weight by this number. That is the tension on the block.“ This shows that the pupil knows how to use the block and tackle correctly, has understood the basic principle and can correctly formulate it in a sentence.

In the textbook, however, this will be expressed for good physical reasons as follows: “Where the moving blocks are held in place by n sections of rope, it will be sufficient – ideally in the absence of friction – for the small force that needs to be exerted to be, as a relation to the bearing force: F = 1/n FL.“ (Dorn/Bader 2016)

It is only possible to understand the way this is expressed in the textbook if one already has considerable knowledge of the matter in question, i.e. in this case the laws of physics relating to a block and tackle system. This confirms the statement made above, namely that the technical language is the language used once the subject content has been understood, while the language of instruction – in this case the way it is expressed by the pupil – is the language used to support the process of understanding. A statement that has been understood cannot be expressed in any more precise terms that the speaker’s individual structure of thought allows. The pupil’s phrasing needs to be expanded by meta-reflection to encompass the technical language level.

CLIL teaching is not good per se – it only fulfils its purpose if it enables the learner to understand the subject. If not, it is counterproductive and results in the aforementioned vicious circle. The language of instruction – being the language used to support the process of understanding – plays an especially important role in this context.

Conclusion

Successful CLIL lessons achieve a double learning effect through language learning in a subject context. The foreign language is learnt in a real-life situation, based on and using the subject content. The language usage situations are determined by the subject and entail specific language obstacles that pose a particular challenge in CLIL teaching. In this respect CLIL lessons can learn a great deal from the foreign languages. Success is the only justification for CLIL lessons, and success is achieved when learners understand the subject content. The language of instruction – being the language used to support the process of understanding – plays a key role in this context.Literature

- Dorn / Bader (2016): Physik SI - Ausgabe 2016 für Rheinland-Pfalz. Braunschweig: Schroedel

- Funk, Hermann; Christina Kuhn; Dirk Skiba; Dorothea Spaniel-Weise; Rainer Wicke (2014): DLL 4: Aufgaben, Übungen, Interaktion. München: Goethe-Institut; Klett-Langenscheidt

- Krashen, Stephen (1985): The Input Hypothesis: Issues and Implications. London, New York: Longman

- Le Pape Racine, Christine (2004): Immersion im Fremdsprachenunterricht - ein Widerspruch? In: Fremdsprache Deutsch, S. 52-57

- Leisen, Josef (1994): Handbuch des deutschsprachigen Fachunterrichts (DFU). Didaktik, Methodik und Unterrichtshilfen für alle Sachfächer im DFU und fachsprachliche Kommunikation in Fächern wie Physik, Mathematik, Chemie, Biologie, Geographie, Wirtschafts-/Sozialkunde. Bonn: Varus

- Leisen, Josef (2003): Handbuch des Deutschsprachigen Fachunterrichts (DFU). Bonn: Varus

- Leisen, Josef (2013): Handbuch Sprachförderung im Fach - Sprachsensibler Fachunterricht in der Praxis. Stuttgart: Klett-Sprachen

- Leisen, Josef (2017): Handbuch zur Fortbildung im sprachsensiblen Fachunterricht. Stuttgart: Klett-Sprachen

About the author

Foto: Privat, Josef Leisen

It was his many years of experience of teaching subjects in German at a German School Abroad to children and young people whose mother tongue was in almost all cases not German that prompted the author to develop language-sensitive content teaching. The works he has published constitute the standard literature on language-sensitive content teaching.

Foto: Privat, Josef Leisen

It was his many years of experience of teaching subjects in German at a German School Abroad to children and young people whose mother tongue was in almost all cases not German that prompted the author to develop language-sensitive content teaching. The works he has published constitute the standard literature on language-sensitive content teaching.

What characterizes his work is that, being a scientist, he approaches the topic from the perspective of the subjects, specialist didactics and content learning rather than from the viewpoint of linguistics. This is what makes his research and work particularly persuasive.

As the former director of the teaching training department in Koblenz and a professor of didactics in physics at Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, the training and further education of teachers is particularly close to his heart. He is in great demand as a lecturer and trainer in language-sensitive content teaching. Essays and materials are available for download from the website:

Sprachlernen im sprachsensiblen Fachunterricht