Holger Wendlandt

THE GERMAN-LANGUAGE ABITUR IN HUNGARY: A CONTEMPORARY MEANS OF ENCOURAGING PUPILS

Hungary has a long tradition of bilingual teaching at its grammar schools. Every year, some 1,000 pupils take a “German-language Abitur” (Germany’s higher education entrance qualification), which generally involves taking a written examination in German in two subjects. This article studies the effectiveness – in terms of both content and language teaching – of bilingual classes in Hungary. To this end, it analyses the publicized results of one entire Abitur year. Possible reasons for the significantly better results achieved by the bilingual students are discussed.

introduction

In recent decades, foreign language skills have become increasingly important. The expansion of the EU has contributed to this trend. In the “Action Plan on Language Learning and Linguistic Diversity“, promoting foreign-language content teaching is proposed as one means of improving language proficiency: “The CLIL approach, whereby students learn a subject through the medium of a foreign language, has a major contribution to make to the Union’s language learning goals.” [European Commission, 2003, p. 11]This article provides an overview of the effectiveness of foreign-language content teaching in the target language of German [1] in Hungary on the basis of data from the 2010 Abitur year.

the bilingual Abitur in HUngary

The first grammar schools to offer subjects taught in German were introduced in Hungary in 1987. This form of teaching had already existed prior to that point for German ethnic minorities. Pupils who opt for this approach are required to take two additional Abitur exams – besides the subject of German itself – in German. The examinations are set centrally. Since 2007, the individual results of all Abitur examinations nationwide have been collected and published as anonymized data sets. [2] Given the huge importance of Abitur results, these data can be seen as very reliable.the number of Abitur exams and Abitur students in 2010

Approx. 2,413 written Abitur exams [3] in the target language German were taken in twelve different subjects at subsidiary course level (közöp szint) in 2010. [4] Because the majority of Abitur students take precisely two subjects in the target language, it can be concluded that roughly 1,200 students took a German-language Abitur in the summer of 2010. [5]By way of comparison, only roughly 2,400 exams in the subject German at advanced level (emelt szint) were taken in all during the period in question.

selection of Abitur subjects

Figure 1 shows the German-language Abitur exams, broken down according to the selected subjects.With the exception of Civilizáció (this subject focuses mainly on the culture of German-speaking countries), history, maths and geography are the subjects most commonly taken in German.

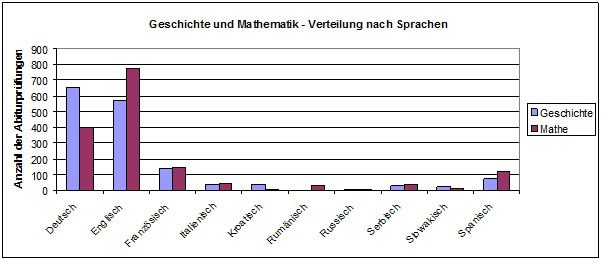

It is interesting to compare the subjects of maths and history with other target languages. As can be seen in Figure 2, the subject of history tends to be chosen in the traditional minority languages. This is presumably because this subject plays a part in shaping the identity of the minority in question. Maths is chosen most frequently in the other target languages (English, French, Italian, Spanish). This is probably due primarily to the importance of the subject for learning the language.

“When it is a question of fostering tolerance and understanding of the other culture [...], such [social science] subjects are ideal. Where the primary goal is to teach language skills, however, subjects that can be presented easily through images and direct demonstration tend to be more suitable.” (De Cilla, 1994, p. 17)

the abitur results

To assess the success of bilingual teaching, the most important thing is the results achieved by pupils in these classes as compared to pupils taught in their native language. A comparison is possible because the Hungarian Abitur is set centrally, and all results are collated and published. Figure 3 compares the average results achieved in the written Abitur examination in 2010 (subsidiary course level) by pupils taught in German and those taught in their native language (Hungarian).As can be seen, the results achieved by the bilingual pupils tend to be significantly higher than average. The difference is most pronounced in mathematics (14.7 percent). A similar tendency to achieve better results is also found when the results of the technical middle schools are compared with one another. This applies (almost) throughout for all target languages. By way of examples, Figure 4 presents the results of mathematics exams in the various target languages (subsidiary course level in each case). [6] Á. Vámos found similar results for the 2008 Abitur year [Vámos, no year given, p. 7f). In other words, the available data show that the subject results achieved by pupils taught in the target language are (almost) always better than the average results achieved by pupils taught in the native language.

One initial hypothesis about the reasons for this might be that the higher average age of the pupils taught in the target language [7] leads to better results. Using the available data, however, it is possible to isolate a native language parallel group with a comparable age structure. It is clear that the results of this parallel group do not differ significantly from those attained by the Hungarian group as a whole. It can therefore be concluded that age does not play any (decisive) role.

language requirements

What impact does teaching pupils in a target language have on their language skills? Empirical studies have been conducted in Germany to examine the linguistic effectiveness of bilingual teaching in English. In this context special mention should be made of the DESI and DEZIBEL studies, both of which conclude that the language skills of pupils in bilingual lessons significantly exceed those of their fellow pupils. Although no empirical studies of this kind have been conducted in Hungary, it can be assumed that bilingual teaching will also achieve similar effects here.It is useful in this content to assess the language level of the Abitur examination. It should be noted that the Abitur questions for the target language pupils are simply translations of the original Hungarian questions. This ensures that pupils have to meet comparable requirements in terms of subject content. At the same time, it means that the linguistic requirements are also comparable, and in both cases are at native proficiency level (the translations are checked by a proof reader to ensure that they are correct in terms of both their general and technical language).

Written Abitur exams are highly text-based in all subjects. This is already obvious from the length of the examination questions: the examination papers alone cover 39 pages in history [8], 16 in geography and 12 in biology. Some questions are based on texts of more than half a page in length. Even the format of the questions requires a high degree of language proficiency, in other words.

In certain cases the linguistic component may prove useful to pupils. The following question from the 2010 Abitur history paper shows an example: parts b) and c) can be answered correctly simply by paying attention to the preceding article. Such cases are the exception, however.

In the subject of history, it is useful to compare the results of the two test sections “questions with short answers” and “essay questions”. [9] This reveals that the basic average scores achieved in these questions by native speaker and German-speaker Abitur students are equivalent. [10] It can be concluded from this that the language skills of the target language pupils are similarly distributed to those of the native speaker pupils.

Because the Abitur is geared primarily to general competence, the amount of language/text to be found even in the subject of mathematics is relatively high. Even here there are questions that cover more than half a page of text. A high degree of text comprehension is therefore also necessary to answer questions in this subject.

looking back and looking ahead

What are the reasons for the above-average results? On the one hand, they are inherent to bilingual learning [cf. Wolff, 1996], they are due to the competence and dedication of the teachers [11], and in many cases are thanks to schools creating a stimulating and challenging profile for themselves. However, the pupils themselves should not be forgotten either – they work hard to meet the challenges they are set, and thereby achieve above-average results.Against this backdrop, such educational approaches can be seen as a means of fostering gifted pupils. As such, they are an important element of the current educational landscape, and should be maintained and promoted in every respect.

There is scope for improving the framework conditions in many respects. The Central Agency for German Schools Abroad (ZfA) [12] for example has been promoting German-language subject teaching in continuing education for teachers for many years. Greater support from the Hungarian authorities would be welcome in this context.

There is also further scope for promoting the value of and raising awareness about these educational approaches. The “CertiLingua-Exzellenzlabel” project [13] can be cited as one example. A similar initiative in Hungary could improve the image and increase the importance of bilingual education.

Anmerkungen

[1] The abbreviation “DFU” is also frequently used: Deutschsprachiger Fachunterricht (German-language subject teaching).

[2] https://www.ketszintu.hu/publicstat.php

[3] This figure also includes Abitur exams in ethnology despite their having a different format.

[4] There were only 25 exams in history and two in mathematics at sixth form level in 2010.

[5] Approx. 360 of these were at a technical middle school.

[6] The results in the target language Russia buck the trend. However, it is important to note here that only four Abitur exams were taken in this language in the Abitur period in question.

[7] Almost all pupils took their Abitur mathematics exam in English, German, French, Italian and Spanish after 13 years of school because they generally spent one year on language preparation.

[8] The length of the Abitur questions in history is also due to the fact that all sources are provided in both the target language and the native language.

[9] The essay questions demand productive language skills. Correct use of language is one of the criteria for assessment.

[10] The average grade achieved in the 2010 Hungarian Abitur was 1.66 and 1.62 in the German-language Abitur.

[11] Based on my personal assessment as a long-term expert adviser at the Central Agency for German Schools Abroad (ZfA) in Hungary.

[12] For details of the activities in the area of mathematics, see: Deutschsprachiger Fachunterricht

Fachgruppe für Physik, Mathematik und Informatik

[13] CertiLingua

Literatur

De Cilla, Rudolf (1994): Was heißt hier eigentlich bilingual? Formen und Modelle des bilingualen Sachfachunterrichts. In: Koschat, Franz / Wagner, Gottfried (Hrsg.): Bilinguale Schulen – Lernen in zwei Sprachen. Bundesministerium für Unterricht und Kunst. Wien 1994. S.11–23.

Kommission der Europäischen Gemeinschaften (2003): Förderung des Sprachenlernens und der Sprachenvielfalt: Aktionsplan 2004 – 2006. Brüssel.

Vámos, Ágnes: The function of foreign language at the school-leaving examination and language-of-education pedagogy in bilingual education. Unveröffentlichtes Manuskript. Ohne Jahr.

Wolff, Dieter (1996): Bilingualer Sachfachunterricht: Versuch einer lernpsychologischen und fachdidaktischen Begründung. (Vortrag am 21.11.1996 an der Bergischen Universität Gesamthochschule Wuppertal. Unveröffentlichtes Manuskript).

about the Author

Holger Wendlandt is a teacher of maths and physics who has spent many years teaching at schools abroad. From 2006 to 2011 he worked as an expert adviser on German-language subject teaching in Hungary, and was the ZfA’s Regional Continuing Education Coordinator for Croatia, Romania, Slovakia and Hungary. He currently teaches at a grammar school in Northern Germany and at Kiel University. Holger Wendlandt has extensive experience in teacher training and continuing education as well as in writing textbooks, and for some years has worked for the Goethe-Institut as an external adviser for early German.