Old Patent Office Building / Donald W. Reynolds Center for American Art and Portraiture

German Roots in DC

-

Old Patent Office Building, August 2010. -

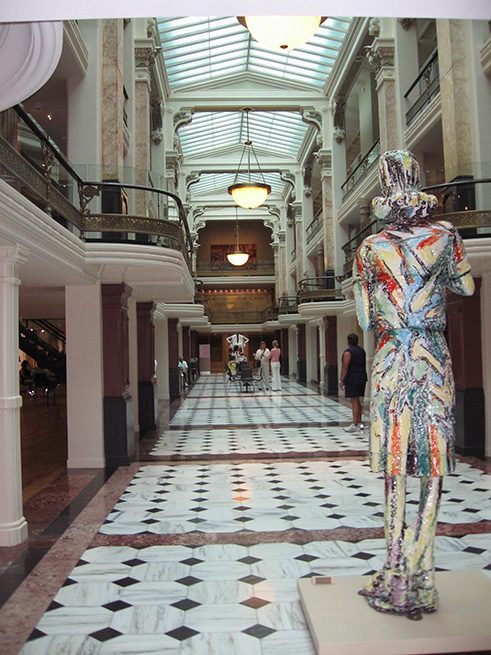

Old Patent Office Building interior 2006. -

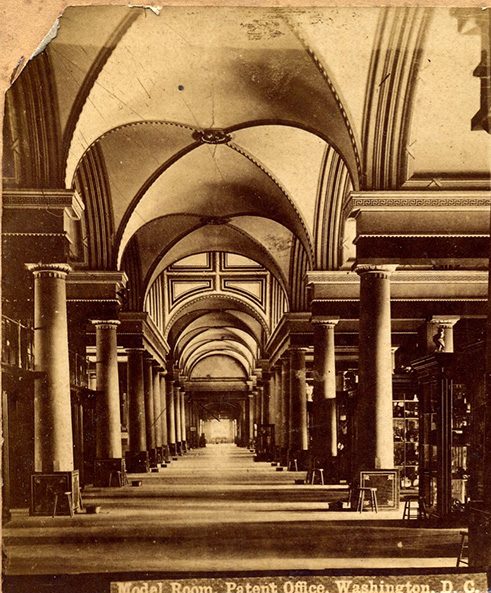

Old Patent Office Building interior. -

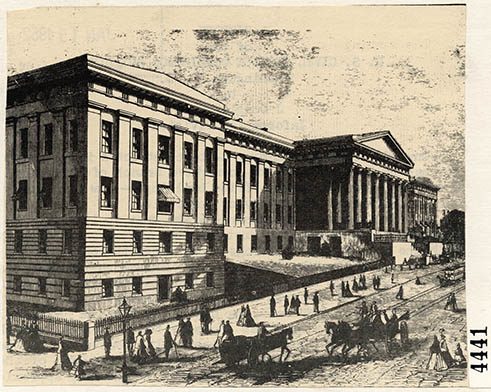

Old Patent Office Building, 1856.

In 1877, around the beginning of Schurz's tenure, a fire destroyed the third floor and attic of the west and north wings. The renovations to the building were carried out by fellow German-Americans Adolf Cluss and Paul Schulze. Certainly Cluss and Schurz would have known each other well since both were actively involved in the failed 1848 revolution in Germany and both were politically active and wrote for newspapers.

As part of the renovation work, Caspar Buberl, the Bohemian-born artist known chiefly for his work on the Pension Building, created the relief panels on the north wall (allegories of Fire, Electricity and Magnetism, and Water), on the south wall (Agriculture, Industry and Invention, and Mining), and roundel portraits of American inventors (Franklin, Jefferson, Robert Fulton, and Eli Whitney) in the Patent Building's model hall.

Adolf Cluss, Architect

born Heilbronn, 1825died Washington DC, 1905

Adolf Cluss dominated Washington's architectural scene from the mid-1860s to his retirement in 1890. As a city planner and engineer, he also helped to shape the very appearance of the city's streets and houses. Yet most Washingtonians today know little of this German immigrant's work, or of his youthful activities as a Marxist writer and organizer during and after Germany's Revolution of 1848.

Cluss broke into the field of architecture in Washington at the age of 39, when he and his partner, Josef Wildrich von Kammerhueber, won a competition for the plan for a new elementary school, the first of eight innovative schools they designed. Two of those buildings survive: the Franklin and Sumner schools. Soon Cluss, alone or with partners, won contracts for many of Washington's major public buildings of the post-Civil War years. Cluss designed three of the four buildings built on the south side of the Mall by 1890, including the Smithsonian Arts and Industries Building (the original National Museum), the only one of the three that still survives. He designed at multiple churches, a hospital, market houses in Washington and Alexandria, and an opera house in Baltimore. His Eastern Market, Masonic Lodge, Calvary Baptist Church, a Fire Station, and one residence in Washington and the City Hall in Alexandria also survived.

Though public buildings seemed to interest him most, he also entered the booming housing market during the Washington's rapid growth after the Civil War. He designed elaborate row houses for the new wealthy class of the city, as well as Washington's first apartment building, almost all replaced in the 20th century by commercial buildings.

As the city's engineer and member of the Board of Public Works in the early 1870s, he superintended the extensive street paving and grading, and the design and building of the city's sewage system. Evidence also suggests that Cluss developed the plan that narrowed Washington's unusually wide streets, and encouraged property owners to plant gardens on the leftover street right-of-way in front of their houses. His plan decreased the city's responsibility for paving and street maintenance, and encouraged homeowners to beautify the city land in front of their houses. He also proposed the regulation allowing construction of houses with bays, porticos, and towers extending four feet beyond the front property lines. With their varied fronts and small yards and gardens, Cluss's proposals made Washington's row houses distinctively different from row houses in other east coast cities. Cluss also suggested the tree planting commission which in the following years planted thousands of trees along most of Washington's streets.

During his professional career, however, Cluss successfully concealed the role he played in his twenties as a friend of Karl Marx and a leader in the communist movement. In biographical accounts Cluss recorded that he was the son and grandson of architects in the German Kingdom of Württemberg, that he worked as a engineer in railroad construction in the Rhine Valley, that he emigrated to the United States in 1848, and moved to Washington, working in several government agencies as a draftsman.

A half-century after his death more facts emerged from European sources. Cluss met Karl Marx in Brussels and joined the Communist League. He became secretary of the Communist League in the city of Mainz, and represented workers as a propagandist and leader in the Revolution of 1848. After the failure of the revolution, Cluss emigrated to the United States. For nearly ten years he corresponded, often weekly, with Marx, Marx's wife, Jenny, Frederick Engels and other leaders of the communist movement in Europe. He wrote articles for German-American newspapers and traveled to participate in worker's meetings. Marx admired Cluss. In 1851, he said, "He is one of our best and most talented men, and the following year, he said of Cluss, "As an agent, the fellow's beyond compare."

By 1858, however, Cluss became disillusioned. There is no evidence of a falling-out with Marx. In fact, Jenny Marx's account of Cluss's visit to London in 1858, apparently to end his relationship with Marx, suggests an emotionally divided man. More likely, the always-practical Cluss concluded that communism had little future in the social and political environment he found in the United States. His employment as surveyor and draftsman for federal agencies, moreover, must have stimulated his professional interests and thoughts of his future possibilities in Washington. His marriage in 1859 also suggests that in a still strange land, he desired the security of a family life.

Becoming a respected and prosperous member of Washington's middle class, Cluss's clients included federal and city governments and wealthy capitalists. He became a friend of President Grant and other political and military leaders. What he thought of the United States' growing labor disputes and violence in the 1870s, or of the publication of Das Kapital, or the death of Marx in 1883 remains Adolf Cluss's secret. Though probably no longer a Marxist, Cluss's devotion to improving the man-made environment of the nation's capital, and building attractive but functional public buildings, suggests that he retained from his youthful idealism and experiences in Germany a vision of a good society.

Joseph L. Browne, Ph.D., Director, Adolf Cluss Project.

Adolph Weinman, Sculptor and Medalist

Born in Karlsruhe in 1870, Adolph Weinman emigrated to the United States as a ten-year-old and attended public schools in New York. At 15, he was apprenticed to a sculptor and attended evening art classes at Cooper Union and, later, the Art Students League. The prominent sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens noted Weinman's talent and later invited the young artist to become an assistant in his studio. Weinman was also an assistant to German-American sculptor Charles Henry Niehaus. Saint-Gaudens was influential in introducing Weinman to the art world and helpful in getting the younger man commissions for various kinds of work creating sculptures and medallions. His work adorns many buildings around the country. In New York, his best known works include the pediments for the Municipal Building (McKim, Mead and White, 1907-1914), friezes for the exterior of the Morgan Library, and the bronze doors fo the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters.He was a member of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, the Architectural League of America, the National Academy of Design, the New York City Art Commission, and the National Sculpture Society, serving as the society's president from 1927 to 1930. He died in Port Chester, New York in 1952.

Weinman's papers are housed at the Archives of American Art.

These notes summarized from an article by Lois Goldreich Marcus in the American National Biography (1999).

Caspar Buberl, Bildhauer

Caspar Buberl was born in 1834 in Königsberg a. d. Eger, Bohemia (now Kynšperk nad Ohří, Czech Republic). His most celebrated work in Washington is the magnificent terra cotta frieze of soldiers and sailors on the exterior walls of the Pension Building, now the National Building Museum.Buberl was also responsible for other sculpture in Washington: "Columbia Protecting Science and Industry" (1881) above the Mall entrance to the Smithsonian's Arts and Industries Building (built as the United States National Museum), and for the relief panels and roundel portraits in the Patent Building's model hall (now home to the Smithsonian American Art and the National Portrait Gallery).Buberl was also responsible for many Civil War memorials, both Union and Confederate, located in places as far afield as Hartford, Connecticut, Buffalo, New York, Richmond, Virginia and Mobile, Alabama. A number of his monuments (to New York battallions) can be found in the Gettysburg National Military Park.