For questions on the function of elites and their relationship to society as a whole, European-American literature on China is of signifying importance: It largely deals with the organization of seemingly absolute power, groups of rigorously educated officials, exceptional scholars, dramatic elite overthrows and potent crowds.

The chart tracks the popularity of China literature in terms of the breadth of its social appeal. The related trend changes during the twentieth century’s first half cycled in quick succession.

Cover picture of Karl May's And Peace on Earth

| Und Friede auf Erden! | © Sascha Schneider, Wikipedia, bearbeitet, CC0-1.0

Early in the century, Karl May’s adventure travel novel And Peace on Earth! – in which a cosmopolitan elite sets the example for a humane world society – and Elisabeth von Heyking’s semi-autobiographical Letters Which Never Reached Him, which portrays German diplomatic and scholarly circles engaging with the social upheavals in China and the USA, found a mass audience. On the cusp of World War I, Alfred Döblin created the intellectual China novel, which made more of an impact in the literary world per se: his eponymous subproletarian hero Wang-lun buys into the critique of power in thinking about possible courses of action in the class and mass society. In the same historical moment, Kafka’s Chinese parables reflect the failure to fulfill the social contract between the “leadership” and individual citizens and the incongruence between expert knowledge and victim experience. Like Döblin’s epic flood of images, Kafka’s tales unfold open narrative processes on unanswerable questions and were discussed by Weimar Republic intellectuals as theoretical-poetological model texts.

Cover picture of Karl May's And Peace on Earth

| Und Friede auf Erden! | © Sascha Schneider, Wikipedia, bearbeitet, CC0-1.0

Early in the century, Karl May’s adventure travel novel And Peace on Earth! – in which a cosmopolitan elite sets the example for a humane world society – and Elisabeth von Heyking’s semi-autobiographical Letters Which Never Reached Him, which portrays German diplomatic and scholarly circles engaging with the social upheavals in China and the USA, found a mass audience. On the cusp of World War I, Alfred Döblin created the intellectual China novel, which made more of an impact in the literary world per se: his eponymous subproletarian hero Wang-lun buys into the critique of power in thinking about possible courses of action in the class and mass society. In the same historical moment, Kafka’s Chinese parables reflect the failure to fulfill the social contract between the “leadership” and individual citizens and the incongruence between expert knowledge and victim experience. Like Döblin’s epic flood of images, Kafka’s tales unfold open narrative processes on unanswerable questions and were discussed by Weimar Republic intellectuals as theoretical-poetological model texts.

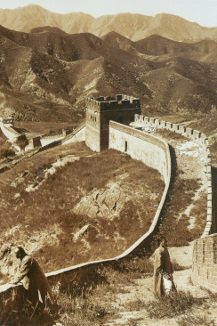

The Great Wall of China, 1907 | © Herbert Ponting, Wikipedia, bearbeitet, CC0-1.0

Literary works on China reached the apex of their popularity with the Pacific War looming on the horizon. Pearl S. Buck’s world bestseller The Good Earth, which struck a biblical note, was turned into a movie by MGM in which the German exile Luise Rainer starred as a Chinese social climber. Vicki Baum, the German-Californian writer, popular for her voyeuristic glimpse behind the façade of the elites, contributed to pro-Chinese wartime mobilization in the USA with her novel Shanghai '37. While Buck and Karl May shared a similar optimism about the productive turnover of ever better elites, Baum even more than Heyking emphasized the insecurity of all social positions in the process of modernity. That the “hard,” turned to stone in the form of an elite, succumbs to other forces is a Taoist teaching with which one of Brecht’s catchy gnomic China poems of the era confronted not only Stalinism.

The Great Wall of China, 1907 | © Herbert Ponting, Wikipedia, bearbeitet, CC0-1.0

Literary works on China reached the apex of their popularity with the Pacific War looming on the horizon. Pearl S. Buck’s world bestseller The Good Earth, which struck a biblical note, was turned into a movie by MGM in which the German exile Luise Rainer starred as a Chinese social climber. Vicki Baum, the German-Californian writer, popular for her voyeuristic glimpse behind the façade of the elites, contributed to pro-Chinese wartime mobilization in the USA with her novel Shanghai '37. While Buck and Karl May shared a similar optimism about the productive turnover of ever better elites, Baum even more than Heyking emphasized the insecurity of all social positions in the process of modernity. That the “hard,” turned to stone in the form of an elite, succumbs to other forces is a Taoist teaching with which one of Brecht’s catchy gnomic China poems of the era confronted not only Stalinism.

For decades after the founding of the People’s Republic, Chinese scenarios formed part of a highly specialized, socio-theoretical debate. Radical voices critical of elites demanding revolutionary pedagogical “self-education of the masses” in the Kursbuch periodical contributed as much to this discussion as did warnings by the hierarchy- and privilege-conscious top diplomat Erwin Wickert against humanity-devouring anarchy. China novels like Wickert’s The Heavenly Mandate and Tilman Spengler’s The Painter of Beijing supplemented these authors’ non-fiction works on China by providing historical case studies on the rise and fall of power, competition among elites and Pied Piperism. They kept alive a literary field that, since the cosmopolitan euphoria of the 1990s and the crises of liberal democracy, has gained again in popularity as an especially pellucid vehicle for designs of social order.

Examples of China Literature

Examples 1:

Karl May:

And Peace on Earth! (original: Et in terra pax,exp., 1901; original: Und Friede auf Erden! 1904)

Elisabeth von Heyking:

The Letters Which Never Reached Him (1904; original: Briefe, die ihn nicht erreichten. 1902/03)

Examples 2:

Alfred Döblin:

The Three Leaps of Wang Lun: A Chinese Novel (1991; original: Die drei Sprünge des Wang-lun,1916,)

Franz Kafka:

The Great Wall of China (1933; original: Beim Bau der Chinesischen Mauer; 1917)

Examples 3:

Pearl S. Buck:

The Good Earth (1931; German: 1933 as Die gute Erde. Roman des chinesischen Menschen; filmed 1937; Nobel Prize for Literature 1938)

Vicki Baum:

Shanghai '37 (1939; German: 1939 as Hotel Shanghai)

Bertolt Brecht:

Legend of the Origin of the Book Tao-te-ching on Lao tse’s Road to Exile (1976; original: Legende von der Entstehung des Buches Taoteking auf dem Weg des Laotse in die Emigration, 1939)

Examples 4:

Erwin Wickert:

The Heavenly Mandate (1961; original: Der Auftrag; English, 1964; exp. 1979 as Der Auftrag des Himmels. Ein Roman aus dem kaiserlichen China)

Tilman Spengler:

The Painter of Beijing (original: Der Maler von Peking,1993)

To the Overview