Cultural architecture in a class all of its own

Well worth seeing - from Hamburg to Bilbao

Many libraries, museums, concert halls and theatres have been brought into the public eye on account of their outstanding architecture. These days, this seems to be more important than ever.

At the opening of Hamburg’s iconic Elbe Philharmonic Hall German Federal President, Joachim Gauck, proudly stated that it was no less than a “real gem for the cultured nation of Germany”. The new concert hall in Hamburg, whose impressive appearance is often compared with the Sydney Opera House, is unquestionably the new landmark of the Hanseatic city.

The construction is one of the highlights of a development that can be observed all over the world. Cultural institutions such as theatres, concert halls and libraries are in fierce competition with the new virtual media. That is why they have to become more and more elaborate and attractive. And they are a real hit when people are fascinated by both their content and their architecture at the same time. The beginning of this development was most certainly triggered by the Centre Pompidou in Paris. One speaks these days of signature architecture, if the visual impact of a building is so impressive, that people never forget it, even if they have only seen the building once.

Just how important outstanding architecture is today has been demonstrated by various cultural institutions that have moved into radiant new premises, and, in doing so, have considerably increased the numbers of visitors. The Tate Modern in London, for example, only managed to have an impact on an international public due to the astonishing conversion of the old power station on the Thames by the Basle architects, Herzog & de Meuron - and was able to repeat this effect once again when an extension was added.

The Bilbao Effect – architecture with a regional radiance

If the effects of the visitors' onslaught are felt way beyond the institution itself, the phenomenon is referred to as the “Bilbao Effect”. In 1997, the new construction of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao by the American star architect, Frank O. Gehry, drew the attention of the culture-interested public to the Basque city of Bilbao. The building functioned as an initial impulse for urban development, as the former industrial estate located on the industrial port has now developed into a prospering district and has opened up new perspectives for this working class city. Every year, one million people visit the city, they constitute a significant economic factor and have given it an enormous boost.The Bilbao Effect is not always so pronounced, but when, for example, in 2015 the Ozeaneum was added to the German Oceanographic Museum in Stralsund, it attracted 852,000 visitors and this moved the museum into second place in the German visitor statistics after Dresden Castle. This, of course, also meant that the Hanseatic city of Stralsund also profited to quite a considerable extent. The Ozeanum, designed by the firm of Behnisch Architekten, was also endowed with that special measure of spectacle that is necessary for the Bilbao Effect. The building has an extravagant shape with a definite recognition factor, it is in a picturesque location on the port and the exhibition it houses is extremely popular.

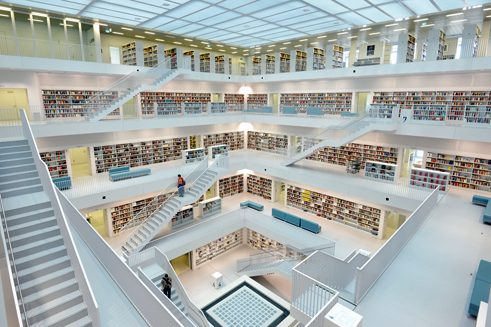

Libraries as places of significance

What is surprising is that in these days of the supposedly paperless IT era new university, municipal and country libraries are still emerging, and they often turn out to be architectural jewels. In 2001, for example, the city of Stuttgart, near the central station in the district of Stuttgart 21, built an unusually designed temple of books with a striking interior. It was created by the Korean artist, Eun Young Yi, and in the evenings it is famous for taking on a blue glow. The Sächsische Landes- und Universitätssibibliothek (SLUB) designed by Ortner & Ortner Baukunst Berlin / Vienna is hardly any less impressive than the Municipal Library in Stuttgart. Max Dudler's library at the Humboldt-Universität in the district of Berlin-Mitte, the Jakob-and-Wilhelm-Grimm-Zentrum, a brick building directly on the suburban train viaduct, are also in the same league when it comes to great architectural experiences.They all have one thing in common – they are exceptionally well frequented, sometimes even overcrowded. Particularly in this age of digitisation, the “library location” is becoming increasingly important: as an educational and information centre, as a place for learning and professional exchange - and as a place where people enjoy spending their time. For this reason, architects like to enhance the library function with lounges, cafés and a wide range of other services. This is not a German phenomenon. Seattle, Birmingham and Aarhus are all home to eye-catching new buildings. No way are they mere halls of books with reading areas, but neighbourhood focal points with all kinds of extra services, with restaurants and studios, with various entertainment and event programs.

Concert halls – even for visitors who do not have a ticket

As with libraries, in concert halls the trend is also towards multifunctionality. These cultural facilities have become social meeting points where people like to spend time - also for those people who do not have a concert ticket. That is why the architectural appeal is of particular importance to these “informal” visitors.An impressive example of this is the music and event centre, CKK Jordanki, in Torun, Poland. The Spanish architect Fernando Menis designed it as an expressively shaped cavelike structure made of bricks. With its crystalline forms the Casa da Música by Rem Koolhaas in Porto also sparkles like an oversized diamond, prominently located at the roundabout of the Jardim da Rotunda da Boavista.

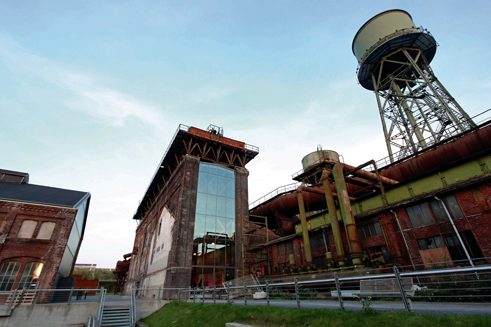

Conversions – the cathedrals of the industrial age as cultural attractions

Every now and then, the financial feat of strength required to convert former industrial facilities into cultural centres comes off. The result is usually a place of great architectural charm – the former Zollverein coal pit in Essen, for example, is today a vivid monument to the coal and steel industry, a museum, an event venue and a university, all at the same time. Or the Jahrhunderthalle in Bochum, a former blasting hall from 1902, which in 2003 was transformed by Petzinka Pink Architekten into an unusual venue for the Ruhrfestspiele (the Ruhr Cultural Festival).In Dresden, a large combined heat and power plant, abandoned in 1994, blocked urban development in the western inner city area. In the meantime, the area has been transformed into a cultural site. “Cathedrals of industry” is what they call the towering, chimney-crowned, brick-built blocks from the 1920s and 1930s. The huge boiler-house was demolished, but has in fact now been replaced by a new building for the State Opera and the Junge Theater, which, with its rusting steel and glass façade, fits perfectly into the industrial landscape. The former machine hall now houses the Studiobühne theatre, the Marionette Theatre and the foyer, which serves all four theatres. The remaining architecturally attractive buildings left over from the power plant have either already been or are still going to be renovated and reused. The art gallery, the energy museum, the creative centre and the restaurants form a lively urban mix with the theatres. With its Kulturkraftwerk, Dresden has gained a second cultural centre and this has somewhat weakened people’s fixation with the traditional tourist zone on the banks of the river Elbe, stretching from the Semperoper Opera House to the Albertinum Palace.

Cultural architecture as a location factor

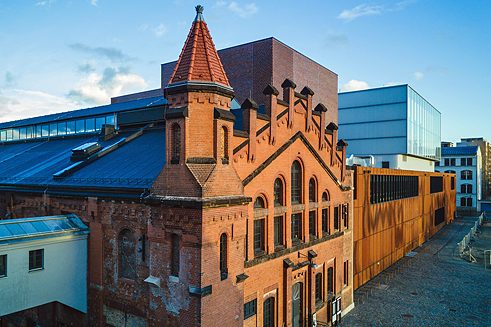

It is not just the big cities like Hamburg that are experiencing their new cultural buildings creating a spirit of optimism among their residents and a new kind of external perception. The effects are also being felt in the provinces. Up to now hardly anybody had ever heard of Blaibach in the Bavarian Forest. Then the Munich architect, Peter Haimerl, came along and built a concert hall there, which in the meantime has won several architecture prizes. And in no time at all the place is suddenly on the agenda for music lovers - at least in the region. In Chemnitz, the splendid State Museum of Saxony for Archaeology has become a destination for both tourists and architecture fans, because it was installed in the famous Schocken department store that was designed by architect, Erich Mendelsohn.Today, culture has become an important location factor, especially when, for example, a city or a region has to compete with other locations to recruit qualified employees. New cultural buildings not only inspire the cities and municipalities, but also cultural professionals and architects - even if the Bilbao Effect does not always kick in.